What are some issues underpinning the choice of a format shape (i.e. outer boundary) for an image?

To thoroughly address the issues involved in formatting an image, the range of format shapes (or lack of a boundary at all) would necessitate tedious and repetitiously listing of similar issues. Moreover there is also the phenomenon that the digital age has brought a new meaning to what constitutes the boundary edge of an image—at least from the audience’s viewpoint. After all there is no longer a tangible support sheet of paper or canvas that sets the outer limits for an image. Mindful of the above realities, I have limited the scope of the following discussion to the following format shapes in the hope that most of the key issues concerning formatting of images will be addressed: an image with a delineated boundary (i.e. a borderline around the image); a polyptych (i.e. a group of images abutting each other that may be read individually in terms of their composition or as a single cohesive group composition); a vignette (i.e. an image fading away from the centre); and, a free-form boundary (i.e. a border created by the pictorial requirements of the subject).

Regarding the first of these boundaries (i.e. a borderline marking the outer edge of the image), the earliest woodcuts invariably feature a bold borderline, such as the Christoffel van Sichem II’s Saint Paul (shown below and discussed in the earlier post, Van Sichem II: Advancing & receding forms). One reason for using a solid line around a woodcut image is certainly to separate the image from potentially distracting imagery or text surrounding it, but there is also a practical reason: the printing process involved in creating a woodcut impression “needs” the borderline. This is because the solid edging of wood on the woodblock that produces the printed borderline acts as a physical support during the process of inking and pressing the print to ensure that the ink is distributed evenly. Moreover, without such an edge the finely cut lines further within the image would crumble very quick during successive printings as there would not be a supporting rim of wood taking the impact of the printing process.

For example in Hans Springinklee’s The Ambassadors of Emmanuel, King of Portugal, demanding the Hand of Eleanor, eldest daughter of Philip I of Castile (shown below) the print is a composite of two plates and no borderline exists where the plates abut each other. To fully appreciate the importance of the outer framing line, compare the sharpness of the printing where the imagery is close to the borderline (see details A and B shown further below) with the areas towards the centre of the print which do not have a borderline support (see detail C also shown below).

|

Hans Springinklee (c.1490/95–c.1540)

The Ambassadors of Emmanuel, King of Portugal, demanding the Hand of Eleanor, eldest daughter of Philip I of Castile, 1515–1518

from the 1775 edition of Weisskunig, plate 156.

Woodcut in two sections

This print is a composite image taken from two separate blocks with two versions of the smaller block allowing for three different printed variations (see The Fitzwilliam Museum catalogue entry for this print: http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/opac/search/cataloguedetail.html?&priref=129820&_function_=xslt&_limit_=10 [accessed 27.10.2012]).

Condition: strong impression on paper with no foxing or blemishes. There is a previous collector’s ink stamp on verso, along with pencil and ink inscriptions and mounting hinges. The original packaging for this print (no longer available) showed the following inscription that may provide authenticy and printing state information but I am not familiar with these catalogue sources: “C.D.I., 374, 4 (1); Put 220 v." I am selling this print for ... [deleted] including postage and handling to anywhere in the world. Please contact me using the email link at the top of the page if you are interested or click the “Buy Now” button.

|

|

Detail C of the unsupported centre area of Springinklee’sThe Ambassadors of Emmanuel, King of

of Philip I of

|

With regard to the formatting of a polyptych, the boundary edge separating each panel in a multi-panelled overall image serves two vital functions. First, the abutting edge of each of the panels helps the viewer to visually digest what may be a large and conceptually complex image into smaller more easily negotiable portions to contemplate and understand. Consider, for instance, the difficulty in reading the text and images interspersed in the pages from a nineteenth-century Japanese woodcut book shown below and compare this sea of visual information with the text and images separated into abutting panels in the three pages from Gountei Sadahide’s (1807–1873) The Chronicle (shown further below).

The second important function is all about visual dialogue. Here, the abutment of each panel with the next invites the viewer to see relationships among the displayed features of the panels and to correlate the projected meanings of all the panels into a single collective multi-layered meaning—a bit like two people on either side of a river noticing each other and starting a conversation. The critical difference between a collection of artworks wedged together and a polyptych lies with the concept of visual dialogue: the collection of artworks wedged together can only be conceived as a polyptych if there are conceptual links uniting them as a composite whole. There is also a difference between a large image that is simply broken into panels and then reunited and a polyptych with is a composite image of separate but related components.

Sometimes, however, the difference is not so clear. For example, in another nineteenth century Japanese book of woodcuts shown below, there is a borderline around each plate that separates one image from the next. When the book is opened, the portrayed subject in each pair of prints—termed a diptych—is a continuation of the same scene. This would normally mean that these prints are not diptych panels at all, but rather a single image that is broken into two portions. From my standpoint, however, the pairs of prints are diptych panels rather than a single cut image as each plate is a separate unified composition with features clearly intended to be read in visual dialogue with its partner. For instance, both pairs of images shown below feature a figure in one plate responding to another figure in the opposing plate. And, importantly, this portrayed communication between the figures is across the printed borderline and the physical gap of the pages (see details further below).

|

Detail of visual dialogue between figures

|

|

Detail of visual dialogue between figures

|

Regarding the third type of image format—the vignette—the all important issue is to fade the image from a point of fixation usually arising from a binocular viewpoint. By this I mean, looking at the subject with two eyes where the focus is narrowed to a point while away from this point, in a full 360 degrees, the focal clarity diminishes. An example of this approach to the vignette format may be seen in Wilhelm Hecht’s (1843–1920) etched portrait of the German painter, Carl Piloty (shown below). Here, the viewer’s attention is focused on the Piloty’s face, partly because it is positioned towards the centre of the plate mark on the vertical axis and also because the treatment of the facial features are so finely rendered in detail. As the viewer’s eye strays away from this area of high focus down the subject’s coat and away into the background, the treatment of the surface details becomes progressively more about loosely laid strokes than with showing intimate details of the subject (compare the details further below).

|

Detail of Hecht’s Carl Piloty

|

|

Detail of Hecht’s Carl Piloty

|

|

Detail of Hecht’s Carl Piloty

|

Another use of the vignette is to recreate the effect of tunnel vision—arguably, a peculiarly male type of vision arising from the primordial hunter’s targeted focus. As an example of this curious phenomenon of tunnel vision, John Moyr Smith’s (1839–1912) Macbeth and Macduff (shown below) is ideal. By design, the print focuses attention on the two outstretched arms of the protagonists at the centre of the image by progressive darkening and distorting the scene towards the peripheral rim (see details further below). This treatment of the outer boundary raises the question that is not often addressed by artists: how should artists portray subject material at the outer field of their vision—the peripheral rim? Of course this seemingly simple question raises a host of other closely linked questions relating to the various vision types such as day vision (also known as phototopic, cone and colour vision) and night vision (also known as scotopic, rod and peripheral vision).

|

Detail of John Moyr Smith’s Macbeth and Macduff, 1889

|

|

| Detail of John Moyr Smith’s Macbeth and Macduff, 1889 |

|

| Detail of Legros’ Portrait de G.F. Watts RA |

|

| Detail of Legros’ Portrait de G.F. Watts RA |

|

| Detail of Legros’ Portrait de G.F. Watts RA |

|

Detail of Legros’ Portrait de G.F. Watts RA

(left) initial strokes before the line of text is added

(right) the same strokes softened (burnished) after the line of text is added

|

The final type of format I wish to discuss is not really a format shape at all but rather an inevitable outer boundary to an image dictated by the subject’s physical dimensions. For example, the hand-finished offset lithograph prints, Oncidium Crispum and Stenocarpus Cunningham (shown below), at first glance look like they both have rectangular format boundaries suggested by the portrayed plants having been pictorially cropped on all sides. On closer inspection, however, this perception is not true. In fact the leaves of the plants are depicted as physically cut along with the far right flower stem of the orchid (see details further below). In short, the initial perception of the featured subjects having been composed in a neat rectangular frame is simply an illusion, but an illusion designed to fool the eye nonetheless.

Instead of the tight constraint of a rectangle’s geometrical format, the plants form their own naturally composed frame, which, by the artist’s clear intention, just happens to be like a rectangle. Such a “naturally composed frame” is not limited to the silhouette edge in two dimensions. In the image of the orchid, Oncidium Crispum, for instance, the artist projects the orchid bulbs and the spray of flowers towards the viewer carving in space a three-dimensional format perceived as the outer surface of a free-form volume.

|

Detail of Oncidium Crispum showing cut leaves

|

|

Detail of Oncidium Crispum showing cut spray of flowers

|

|

| Detail of Stenocarpus Cunningham showing cut leaves |

|

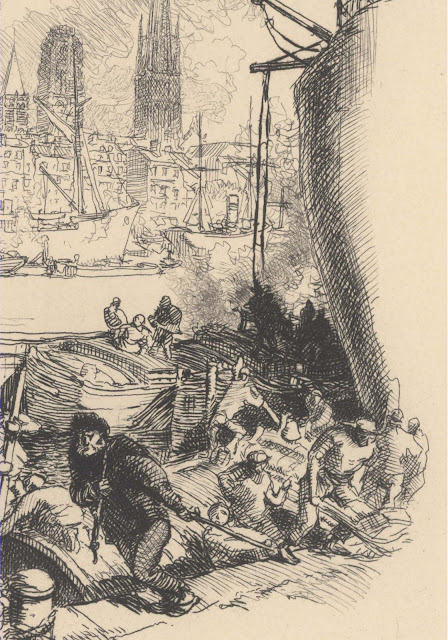

Detail of Lepere’s Un quai à Rouen, 1899

|

|

Detail of Lepere’s Un quai à

|

|

Detail of Lepere’s Un quai à

|

There are so many different types of formats that I could—and perhaps should—discuss; for instance, the tondo (a circular format) and formats where the border annotates the portrayed subject that it frames, such as may be seen in the engravings by Pintz (discussed in the post Expression by Juxtaposition. Although I do not wish to dismiss this consideration, my intention, as I commented at the start of this discussion, is to clarify the issues underpinning just a handful of different types of formatting with the view that the same issues also underpin most of the other format types. Nevertheless, in future posts I will address more formats, as there are some that are very interesting ones that draw upon the world of optical illusions.