What are some of the principles underpinning how artists portray shadows?

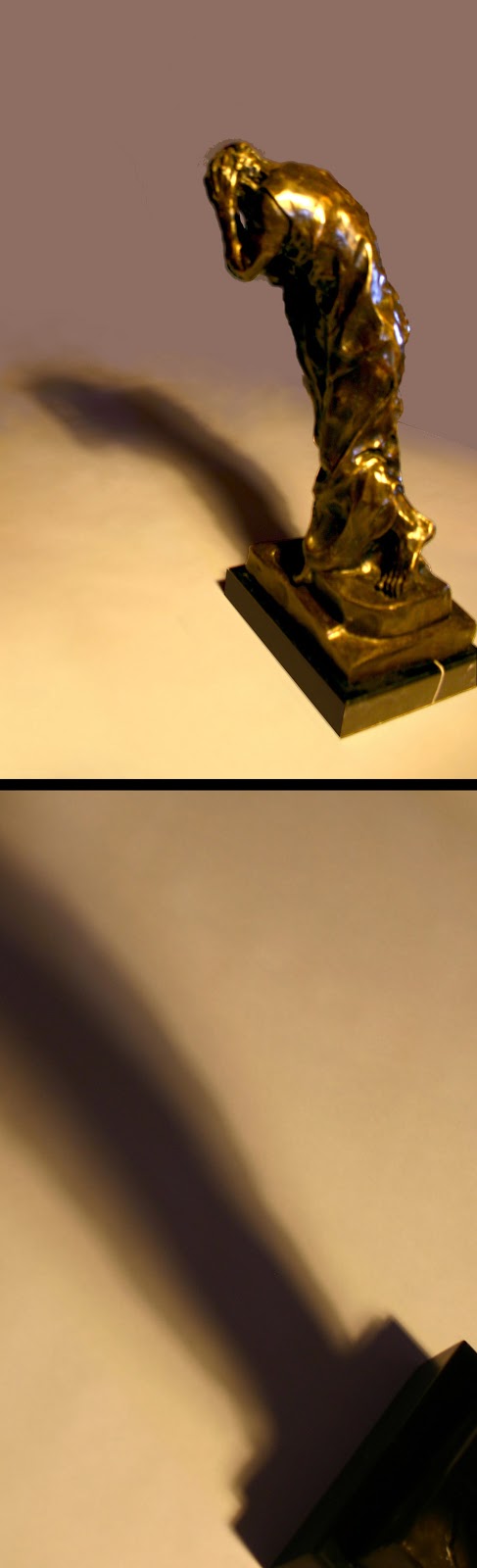

Over the last few years, Auguste Rodin’s (1840–1917) six bronze figures that make up his sculpture group, The Burghers of Calais, have made their way into my life. My studio is now dotted with models, drawings and prints about this moody group of figures and I know that the root of my interest in them is all about the play of light and shadow on their forms. For instance, last night I spent my evening drawing Rodin’s emotionally burdened, Andrieu d’Andres (shown below). My attention focused on modelling the figure’s form out of a mass of dark bronze reflections and shadows set against a stark white background. In short, my present preoccupation with shadows is driving the following discussion. Its focus is on key principles and conventions behind portraying shadows: the principles that artists apply when constructing shadows; traditional approaches used to represent shadows; and, the conventions underpinning chiaroscuro lighting (i.e. theatrically dramatic lighting featuring sharp contrast of light and shadow). As the scope of the topic is large, I will break the discussion into three parts and for the first part I will deal with the construction of shadows.

|

Detail of Auguste Rodin’s Andrieu d’Andres

(one of six figures featured in The Burghers of Calais)

|

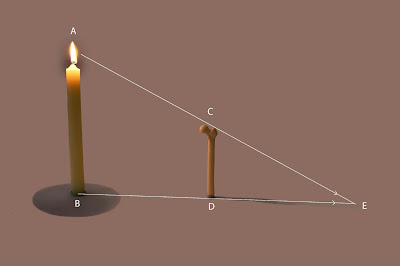

With regard to the principles for constructing shadows on the ground, there are five fundamental points in an image for an artist to establish (see illustration below). The first of these points (see “A” in the illustration) is the centre of the light source casting the shadow. The second point (see “B” in the illustration) is on the ground vertically below the light source. The third point (see “C” in the illustration) is on the portrayed subject from which the artist wishes to cast a shadow. The fourth point (see “D” in the illustration) is on the ground vertically below the previous point. The fifth point (see “E” in the illustration) is at the far end of the shadow.

|

Five fundamental points in the construction of shadows

|

From point A, the artist inscribes a line passing through point C on the subject to mark the farthest point of the shadow cast by point C on the ground. This point on the ground is point E. To determine the angle of the cast shadow, the artist inscribes a line from point B, through point D and the angle of this line establishes the angle of the cast shadow connecting point D with point E (as shown in the illustration below).

|

| Establishing the length and angle of a shadow |

Note that the length of a shadow is determined by the angle of a line inscribed from the light source (point A) to the point on the subject casting the shadow. Essentially, this means that shadows are different lengths depending on this angle of incidence (i.e. the angle determined by a line drawn from the light source that tangentially brushes against the subject). For example, in the illustration shown below the shadow cast by the lit candle is much shorter than a shadow that would be cast from the unlit candle.

|

Shadows vary in length according to the angle of incidence

|

Note also that the angle of a shadow is determined by inscribing a line from the point on the ground (point B) vertically below the light source to the point on the ground vertically below the point on the subject casting the shadow (point D). This allows for a radiation of shadows when there is more than one subject (as shown below).

|

Radiating shadow effect

|

When there is a broad light source illuminating a subject (as opposed to a pin-light for instance) a fractured shadow with three distinctly different tones is cast radiating from the far edges of the light source. In technical terms the dark centre triangle of tone is called the umbra. The lighter outer edge of such a shadow is called the penumbra and the farther out triangle of shadow that is formed is called the antumbra (see illustration below).

|

| Umbra, penumbra and antumbra |

The same formation of an umbra and penumbra also occurs when there are two or more lights (see illustration below).

|

| Umbra and penumbra shadows |

|

Simultaneous contrast (note how the tones are lighter in the centre and darker at the edges of the umbra and penumbra regions)

|

In the next post—Shadows (Part 2)—I will discuss how artists apply the above principles but as a foreshadowing of how the use of simultaneous contrast is applied consider the luminous shadows in Michel Dorigny’s (1617–65) Bacchanal of Children (shown below).

|

Verso

of Dorigny’s Bacchanal of Children

(right

image shows collector’s stamp)

|

|

Detail

of Dorigny’s Bacchanal of Children

|

|

Detail

of Dorigny’s Bacchanal of Children

|

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please let me know your thoughts, advice about inaccuracies (including typos) and additional information that you would like to add to any post.