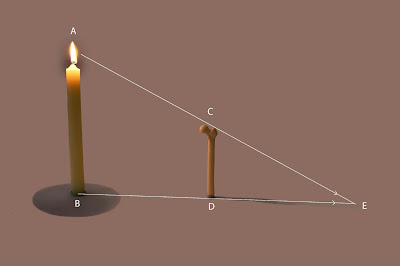

What are some of the principles underpinning how artists portray shadows?

In the previous post about shadows (see Part 1), the focus is on the construction of shadows and some of the subtle principles guiding artists. This present discussion moves beyond the construction phase to explain how tradition has moulded the way artists render shadows (i.e. “shade” them).

Broadly, tradition has given artists two important principles. The first is culturally driven and is arguably the legacy of a culture’s reading direction. For instance, cultures where people read from left to right, such as the Occidental cultures, the Western lighting convention has evolved, as discussed in the earlier post, Drawing Corners. This convention leans artists towards using a top-front-left lighting direction to ensure that the angle of illumination portrayed in images facilitates an audience’s reading direction. In the sensitive and poetic portrait of Paul Véronèse (shown below), for example, the angle of lighting from the top-front-left invites the eye to look first at the illuminated left-side of the Véronèse’s face before moving attention to the shadow side of his face on the right. For an audience with a right-to-left reading direction, such as Arabic or Hebrew readers, the conventional angle of illumination is the converse (i.e. the angle of portrayed lighting in images is from the top-front-right).

The second principle employed is a visual code of mark-making for representing light and shadow that an audience accustomed to looking at art understands (see for example a range of approaches and visual devices for portraying light in the earlier post, Representing light). Tradition has evolved such a visual code in the sense of rendering styles. For instance, fine lines usually connote light whereas thick lines connote shadow. Going further, fine lines that are short, crisp and sparsely laid usually connote very intense light whereas thick lines that are long with very little space between them usually connote intense shadow.

In Piranesi’s dramatically lit etching, Scenographia Pontis hodie Mollis (shown below), for example, the forward projecting stones appear to be glistening in the intense light falling on the time-ravaged bridge (see details further below). This intensity of light is created in part by strong contrast between light and shade, but the intensity of the light may also be attributed to the way Piranesi has rendered the lit surfaces using very fine and short strokes, many of which are no more than dots. Of course their small size and their effect of portraying strong light is only meaningful by comparison to the much longer and thicker strokes rendering the shadows (see details further below).

|

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–88)

Scenographia Pontis hodie Mollis, c. 1760

“View of the bridge known as Ponte Molle, from Il Campo Marzio dell' Antica Roma, Opera di G.B. Piranesi socio della reale società degli antiquari di Londra (The Campus Martius of Ancient Rome, the Work of G.B. Piranesi, Fellow of the Royal Society of Antiquaries, London), plate 39” (see http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/90080757?rpp=20&pg=1&ft=View+of+the+bridge+known+as+Ponte+Molle++Tab+XXXIX&pos=1 [viewed 28.1.2013] and http://www.vialibri.net/item_pg_i/181164-1760-piranesi-scenographia-pontis-hodie-mollis.htm [viewed 28.1.2012])

Inscribed: “Tab. XXXIX.” upper right; “Scenographia Pontis hodie Mollis, ostendens quod remanserat antiqui eperis cum a Nicolao V. Pont. Max. vestitutus fuit. A. Tiberis fluvius.” bottom centre; “Vide indicem ruinar. num. 3.” lower left; “Piranesi F.” [Fecit] lower right.

Etching on laid paper (3cm chain marks without watermark)

22.2 x 35 cm (image); 23.4 x 35.7 (plate); 37.2 x 54.2 cm (sheet)

Taschen 522; Focillon 469; Wilton-Ely 600

|

|

Detail of fine short marks portraying strong light

|

|

Detail of thick long marks portraying strong shadows

|

An effective approach employed by artists to render the dark tones of shadows, especially intensely dark shadows, is to scatter pin-points of white throughout the areas of dark tones. This practice gives optical sparkle to dark shadows by the phenomenon of simultaneous contrast and prevents shadows from being dull spots in an image. The need to create these flecks of white plays a role in an artist’s choice of rendering style. Goltzius' dotted lozenge style of cross-hatching (see the earlier post, Dotted Lozenge), for example, is ideally suited to producing diamond-shaped points of light in full shadow. This principle of ensuring the there is spirit in shadowy darkness is also a fundamental principle in Oriental brushwork. In the detail of a brushstroke shown below, for example, natural breaks in the flow of ink produces and effect called “flying whites.”

|

“Flying whites” in a brushstroke

|

What I find particularly interesting regarding the portrayal of shadows is how the alignment of marks and the inherent attributes resulting from how artists lay each mark contributes to an effective portrayal of shadows. For instance, in Goya’s etching, The Little Prisoner (shown below) and in many of his other etchings, Goya employs horizontal lines to render shadows. Although I have no privileged information regarding his reason for using this horizontal alignment of lines over other rendering styles, from a personal standpoint, Goya’s choice makes sense: horizontal lines connote the idea that shadows “lie down.” Moreover, a pattern of horizontals in the dark regions acts as the perfect foil of calmness to complement the grim subject matter often featured in his prints. This is especially true in The Little Prisoner, as the horizontal alignment of lines portraying the shadowy background contrasts strongly with the contour marks describing the figure.

|

Detail of Goya’s Little Prisoner

|

|

Detail of Goya’s Little Prisoner

|

Another principle guiding artists when portraying shadows is the simple but useful rule: surface details and textures are best shown in the half lights (i.e. those areas on an illuminated subject that are halfway between being in the light and in the dark). Or, to express this rule strongly in a negative way: do not depict a subject’s surface details and textures in the subject’s most brilliantly lit areas or darkest shadows. For example, in Leon Cogniet and Theodore Gericault’s collaborative lithograph, Le Maréchal Famand (The Flemish farrier) shown below, note that the pattern on the horse’s rump is invisible where the light is strongest, but clearly visible in the half-light and invisible in the darkest areas (see details further below). This arrangement is not restricted to the horse and can also be seen in the treatment of the man on left (see detail of his legs further below).

|

Detail of Cogniet and Gericault’s Le Maréchal Flamand

|

|

Detail of Cogniet and Gericault’s Le Maréchal Flamand

|

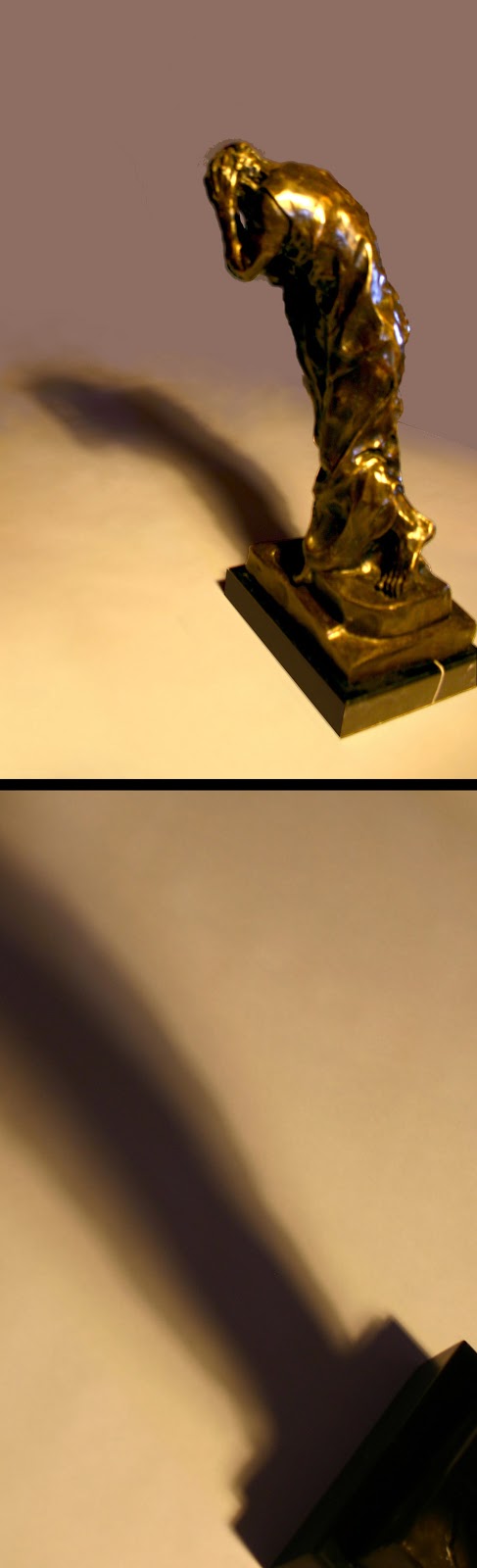

To further ensure that viewers see areas of dark tone in an image as shadow, as opposed to seeing these areas as representing dark colours, artists often employ a subtle but important technique: retroussage. This is a technical term for lightly stroking an inked plate with cloth before it is printed so that ink in the etched or engraved lines is brought to the surface resulting in the effect of blurred lines when the plate is printed. By using this technique, artists can emulate the loss of focal acuity usually experienced when looking into shadows.

A similar effect of focal blurriness to signify shadows may also be achieved by the use of drypoint. This process involves the artist scoring marks to represent shadows into the printing plate so that a burr of metal is raised with each line. Ink catches in these burrs when the plate is prepared and when printed the uneven accumulation of ink caught in the burrs produces velvety-soft lines.

The combination of retroussage and use of drypoint may be seen in the shadowy foreground of Seymour Haden’s Twickenham Church

|

Detail of Wickenham Church showing retroussage wiping

|

|

Detail of

|

The true test of Haden’s success in

representing shadows is as simple as asking the question: would an art

acculturated audience be likely to see the foreground trees in this print as black—perhaps

as the outcome of a fire—or as in shadow? Hopefully the answer will be

affirmative.

In the next post on shadows (Part

3) I will continue the discussion by addressing some of the conventions

underpinning the use of chiaroscuro lighting.

.jpg)