What are some of the principles guiding artists’ use of colour and tone to create the illusion of spatial depth?

|

A rainbow illuminating my desk

|

Let me begin by saying that most folk have an inherent understanding of colour in terms of choosing the best colour for a certain purpose; this includes choosing a colour scheme for portraying spatial depth in an image. If asked to explain their choice, however, the discussion may lean more to personal associations, past experiences and popular expectations that relate to colour rather than pictorial conventions and theories dealing with colour and perception. Mindful that there is little point in addressing colour and spatial depth in terms of personal insights and dispositions—there are far too many variables impacting on the decision process to entertain such an undertaking—the following discussion focuses on three fundamental but closely related principles underpinning most artistic practices: colour perspective, chromatic perspective and tonal perspective. For the sake of clarity, most of the discussion concerns artworks created with paint (i.e. processes that colour theorists’ term “subtractive”) but most of the principles apply equally well to screen-based artworks including those that deal with projected light (i.e. processes that colour theorists’ term “additive”).

|

A rainbow illuminating my desk

|

Regarding the first of these principles, colour perspective, this is probably the most fundamental of all the ways that artists portray depth, as it involves all the hues of the rainbow. Essentially the use of colour to achieve pictorial depth in an image is a simple as saying: “Colours that are warm (i.e. colours like orange, red and all the browns that have associations with heat) should feature towards the foreground and the colours that are cool (i.e. colours like green and blue and all the aqua colours that have association with cold) should feature towards the background.” Such a simplistic statement, however, is only a broad guide and if applied in a formulaic way could lead to a perfunctory and unsatisfying outcome.

In terms of subtleties involved in using colour to achieve spatial depth, ideally an artist ensures that the colours in a composition “live happily with each other”—a poetic expression for a desiring a colour-coordinated image where each colour looks like it belongs and contributes in a cohesive way to a unified overall image. To achieve this colour unity artists often introduce an element of cool colour to a warm foreground and an element of warm colour to a cool background. This may involve literally adding a splash of each colour group to the other (as shown below in my painting, September Garden) or mixing all the colours with a touch of each other so that they all appear to belong to the same colour family (as shown further below in my painting, October Garden). Of course, an artist must be careful when mixing cool colours with warm as such mixtures of complements may result in images with muddy colours resembling army camouflage.

|

James Brown

September Garden, 2011

Oil on canvas

59 x 70.5 cm

[This painting has been sold]

|

|

James Brown

October Garden, 2011

Oil on canvas

59 x 70.5 cm

[This painting has been sold]

|

An important principle in making colours “sing” or “talk to each other” is the choice of colour placed in between. There is an old adage (thankfully ignored by most artists, as from my experience there is little truth to it) that “blue and green should never be seen without a colour in between.” For some artists this may be a useful rule, especially when blue and green play such a vital role in creating the illusion of spatial depth. Like all generalisations, however, the context in which colours are used is critical. Some artists, such as Sam Fullbrook (1922–2004), have no problem with placing strokes of blue and green together and their artworks are undeniably lyrical as a consequence. Of course, in other artists’ hands the same juxtaposition can appear unpleasantly saccharine. In terms of making the two colours sing, or excite the eye, however, there is truth to the adage. For instance, if middle-tone grey is placed between blue and green the abutting edge of grey beside the blue will appear to have an orange colour cast to it while the abutting edge of grey beside the green will appear to be a reddish grey (see colour diagram below). This colour interaction—technically termed “simultaneous contrast”—at the line of abutment is a marvellous way to induce the viewer’s eye to optically see more colours in an image than are really there.

|

Juxtaposition of middle-grey with blue and green

(Interestingly, the blue, grey and green are all the same tone) |

Arguably, Oriental artists have been aware of this phenomenon far longer than in the West, as it is a part of their brush tradition to connote colour without using colour. For example, in Kato Eishu (alias Einosuke, 1873–1939) scroll painting of chickens (shown below), the greyed magenta strokes giving form to the chickens’ comb, wattle and legs do more than simply enliven the painting with a dash of colour. To my eyes, or more specifically to my mind’s eyes, these stokes of colour affect my perception so that I see green in the rooster’s tail, yellow in the hen’s feathers and blue extending behind the chicken family. Even more peculiar, I see the dull magenta as not being a single colour but a full range of warm colours with the head of the hen appearing as scarlet and the head of the rooster as a dull violet-red (see the digital reconstruction with the colours I perceive shown further below.) While I can imagine sceptics wishing to propose that this is nonsense or symptomatic that I may need bucket loads of medication, thankfully Edwin Land’s Retinex theory (also known as the Land Effect) supports my perception.

|

Detail of Kato Eishu’s Chickens

|

|

Detail of Kato Eishu’s Chickens

|

|

(left) original detail of Kato Eishu’s Chickens

(right) digitally altered detail recreating the Land Effect

|

Edwin Land, the inventor of the Polaroid camera, discovered this effect in 1977 (see an excerpt from his talk for the BBC on colour perception below). Essentially, he proposes that our eyes and brain are “wired” to see colour constancy (i.e. our brain ignores changing local conditions in our view of coloured objects, such as cast shadows and reflected light, to ensure that our perception of the objects’ colours is consistent). Going further, our brain and eyes are equipped to add colour where colour constancy is needed. By extension of this fascinating discovery (presuming my understanding of the phenomenon is not too biased to how I wish to understand it), in the case of Kato Eishu’s Chickens, this means that my vision of an almost technicolour reading of what is essentially a monochrome painting is not outside the realms of possibility.

Uploaded by technologizer on May 4, 2011

Excerpt from a 1985 episode of the BBC's Horizons show on colour perception, featuring Polaroid founder Edwin Land.

(For another site that explains the principle in an easy to understand way see: http://www.grand-illusions.com/acatalog/Land_Effect.html)

To test the efficacy of the Land Effect I have digitally reconstructed September Garden below by desaturating its hues (i.e. neutralising the colours to grey) but retaining the centre red flower in full colour. By intention, a viewer should be able to see colour in the surrounding grey tones based on an expectation of what the colours should be after seeing the full-colour image earlier. Whether this envisaged outcome is validated from personal experience or not is open for discussion. If it is validated, then the idea of limiting the number of colours employed to represent a broad spectrum of colours, especially with regard to portraying spatial depth, may be a useful guiding principle for constructing images.

|

Experimental test of the Land Effect

|

Regarding chromatic perspective as a principle to achieve spatial depth, like colour perspective, it can be summed up in a very simple statement: “Saturated colours (i.e. colours that match the rainbow hues in intensity) should feature towards the foreground and colours that are chromatically degenerated (i.e. dull and greyed-out colours) should feature towards the background.” As is the case with colour perspective, however, there is a myriad of subtleties that can make the outcome of applying the principle more inviting than using it in a soulless perfunctory way.

My painting of cactus flowers, Small Lanterns (shown below), for example, features vibrant foreground colours set against a grey background, but the two spatial zones of foreground and background are designed to “talk” to each other. This visual dialogue occurs at the silhouette edge of the flowers and leaves, where the cactus meets the background. Along this line of intersection I have added small accents of darker background tone at points where I conceived that the subject needed pictorial weighting to suggest tension in the cactus’ form. To my eyes, these nodal points bring the background and cactus close to the same spatial plane—as if the background and the cactus are like separate painted ceramic tiles with the dark tonal accents acting like grout joining them together (see detail further below). This connection of spatial planes at the nodal points, in one sense, creates spatial ambiguity by flattening the illusion of spatial depth. In a larger view of the painting as a whole, however, the perception of spatial ambiguity occurs only at the nodal points and, as a consequence of these points of connection, the painting may be seen as a cohesive, unified composition. In short, the subtlety of this device ensures that the key subject of a composition is not divorced completely from its surroundings even though the use of chromatic perspective presents the subject in deep space.

|

James Brown

Small Lanterns, 2011

Oil on canvas

70.5 x 59 cm

[This painting has been sold]

|

|

| Digital accentuation of silhouette edges in Small Lanterns |

Regarding tonal perspective in the use of colour, this principle for achieving spatial depth may be summed up in the statement: “Dark colours should feature towards the foreground and light colours should feature towards the background.” This arrangement of tones is straight forward and it captures the illusion of pictorial depth very well. As is always the case, however, there are exceptions. For example, if an artist wishes to represent the space in a small room the use of the rule would not produce a satisfactory outcome—the room would appear to be very deep. Accordingly, to portray shallow space, as in a small room, an artist reverses this rule and uses light colours in the foreground and dark colours in the background. Similarly in depicting a scene featuring a body of water, if the artist wishes to portray a lake or a wide river then the rule of a dark foreground with a light distance is fine. If, however, the artist wished to portray a small pond, creek or narrow canal then the rule should be reversed.

To demonstrate this phenomenon I will return to Japanese painting and offer the mountain landscape shown below by Tanomura Chikuden (1777–1835) as an image to focus on. Before I start, however, I need to clarify how the tones are used in the painting, because, like all Oriental paintings, side lighting is not used to give a subject form and to create the illusion of three dimensions. Going further the varying tones of black ink in this painting do more than display a grey scale version of a mountainous landscape receding into the distance; the way the brush strokes are laid and the white spaces between them express mood and colour. In fact Tamomura Chikuden’s paintings are famous for representing melancholy by the phrasing and disposition of his marks. In the detail further below, for instance, note how he builds the texture of the mountain by the dot-like deposits of ink that he leaves at critical stages along a line.

|

(left) detail of Tanomura Chikuden’s brush strokes

(right) detail area of the painting marked in red |

In terms of tonal perspective, this painting relies on the same tonal perspective principle as artists use in the West: a dark foreground and a light toned distance. The application of the principle, however, is far from a Western approach. In a broad way, each mountain is presented a tone lighter than the next to achieve spatial depth in accordance with the tonal perspective principles. Nevertheless, each mountain is painted like a stage-flat, with pancake-shallow space, separated from the other mountains by mist.

This perceived flattening of the individual mountains is a conundrum: at first glance, the application of the principle seems to be applied but closer inspection reveals inconsistencies that result in the flattening. For example, in the detail shown below of a cluster of mountain ridges, the lighter aspects of the front ridge are towards the foreground (i.e. the viewer) while the darker aspects are towards the distance—an arrangement that is inconsistent with the perspective principle. The ridges behind the closer one, however, may be viewed as darker towards the foreground (i.e. the centre areas of the ridges) with their lighter aspects at the silhouette extremities—an arrangement that is consistent with the perspective principle.

|

Detail of Tanomura Chikuden’s landscape

|

As an exploratory Western approach to portraying the same mountain I have inverted the tones in the digitally adjusted detail shown below (my apologies to sensitive folk that object to any manipulation of masterpieces).

|

Detail of Tanomura Chikuden’s landscape with inversion of tones and other digital modifications to deepen the illusion of spatial depth

|

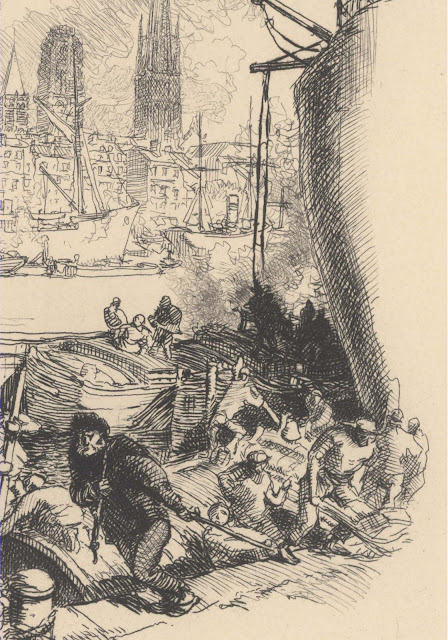

A Western artist’s application of the principle may be seen in E Challis’ engraving of JMW Turner’s The Arch of Titus—Rome

Uploaded

by uoplerta on Aug 13, 2011

The

Adelson Illusion

_____________________

In future posts I will augment

these three perspectives with additional ones, such as, opacity, sheen, shape and

texture perspectives.

Most important, for the first time

I have opened the blog to comments.

Please let me know your thoughts, advice

about inaccuracies (including typos) and additional information that you would

like to add to any post.