Why do some images appeal to our sense of beauty and yet they may be seen as ugly?

I suspect that we all have partners or friends that appear beautiful to us despite our understanding that their faces and bodies do not match current notions of beauty (e.g. a beautiful person should be symmetrical and with attributes that are the perfect average of everyone’s face and body). Such a perception, of course, does not end with the conundrum of seeing beauty in non-beautiful people. For example, my dog—a Staffy affectionately, but inappropriately, called “Cat”—is beautiful. This clear view of gorgeous beauty exists in spite of my cook’s insensitive assertion to Cat while cuddling him: “You are the ugliest dog in the world. Only your mother could love you.” For the present discussion I wish to extend this very shaky proposition that beauty may be of a kind that transcends superficial appearance and move to a more solid argument that the oxymoron of ugly beauty has manifested itself in art: the art of scholars’ stones1 (called “Gong shí” ["respect stones"/"viewing stones"/”spirit stones”] and “Guai shi” [“grotesque stones”] by the Chinese, “Suseok” by the Koreans and “Suiseki” by the Japanese).

On the shelf in my studio is such a grotesquely beautiful stone (see below). It is petrified wood and for me this fossilised stone projects from within its rugged form an aura of spirit, presence and inexplicable beauty. In short, to my eyes it is one of nature’s masterpieces even though I have been told by an insensitive friend that it is simply an ugly old rock. Like all masterpieces there are five fundamental principles that can be used as a check-list of attributes exhibited when determining the aesthetic quality of such stones and these I will explain in the following two-part discussion: shou (thinness); zhou (wrinkles); lou (hollowness); tou (penetrated); and, qi (life force).

The first of the principles—shou (thinness)—as Richard Rosenblum insightfully explains in his marvellous book, Art of the Natural World: Resonances of Wild Nature in Chinese Sculptural Art (2001)2, means that a stone should be “literally ‘skinny’ or ‘emaciated’” and, in sustaining this body metaphor, “a rock should reveal a patterned and strong structure” (p. 143). In short, the attribute of shou revealed in a stone (or whatever the artwork may be) should project the dynamic energy and inner spirit—the qi (life force) that I will discuss later—of the object’s internal structure. In terms of the Chinese leaning to valuing such a quality, Kemin Hu’s opening sentence in The Suyhuan Stone Catalogue: Scholars’ Rocks in Ancient China (2002)3 points out that “Chinese in ancient times believed that rocks were the bones of the world, the essence of qi (energy, or universal life force).”

With regard to my piece of petrified wood, shou is expressed by the elegant silhouette line of the stone’s vertical form and by the way that the rutted roughness of the stone’s surface suggests the rhythm and grain of the stone’s crystallised core—a bit like how the sagging skin of very elderly folk hangs from their bones and reveals the form of the bones. Rosenblum (2001) summarises this phenomenon well when describing a piece of his own artwork “… the sculpture was getting its movement not from its contour but from the forms inside it …” (p. 111). The expression of an object’s unseen interior dynamics is of critical importance to a viewer perceiving its structural beauty (assuming that the object possesses the mercurial element of beautiful ugliness). Moreover, the suggestion of interior forces impacting on the outside has deep philosophical roots as Rosenblum (2001) clarifies: “This concept of an infinite world within a finite form resonates throughout Chinese nature art …” (p. 43).

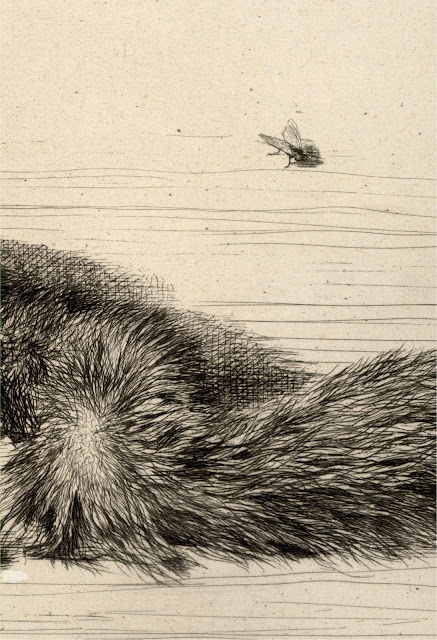

The second principle—zhou (wrinkles)—again draws upon the interior forces within the stone giving form to (i.e. shaping) the stone’s exterior surface, but there is a difference between the related principles of zhou and shou. With the principle of zhou a viewer is invited to contemplate surface attributes of the stone in terms of natural wrinkles that have an intrinsic beauty all on their own. This notion of beauty has led to a host of names for the various types of wrinkles deemed desirable (e.g. jiqu zhou [chicken-bone wrinkles], hutao zhou [walnut wrinkles] and heye zhou [lotus-leaf wrinkles][Rosenblum, 2001, p. 143]), but these variants are only descriptive technical terms created for collectors. The critical attribute of beauty seen in wrinkles lies with the hallmarks of natural forces acting upon the stone’s surface: signs of authentic weathering and patina. According to Rosenblum (2001), “lined, rugged (even ancient looking) texture is best” (p. 145).

Taihu Lake

|

Evidence of zhou where the core of the stone shapes its surface contours

|

My piece of petrified wood, for example, showcases the attribute of zhou by the naturally occurring, but now fossilized, rotted surface of the original timber (see details below). For me, the petrified wood exemplifies very well the desired qualities of “lined,” “rugged” and “ancient looking.” Moreover the twisting—almost spiralling—rhythm of surface corrugations projects outwards the suggestion of rhythms beyond those that may be physically mapped on the stone (see illustration further below). This conception of the stone being seen to connect by its twisting rhythms to the infinite beyond may also help to explain its aura of being “special” in the sense that it embodies the spiritual essence of a world larger than itself. This idea is not of my own concoction, as Vincent Covellow and Yuji Yoshimura (2009) in The Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation: Suiseki and its Use with Bonsai 4 explain:

According to the teachings of Zen, everything finite tells of the infinite, and everything animate and inanimate is the product of the same force. By mediating on the stone, a monk could understand the essence of the stone, the essence of a mountain, and all else in the universe. To experience this essence, to become one with the stone, was to become enlightened. (p. 20)

|

Digital exploration of the rhythms suggested by the stone

|

The third and fourth principle—lou (hollowness) and tou (penetrated)—are also inextricably linked with the previous principles and the philosophical concepts underpinning them; related concepts that may be summed up with Rosenblum’s (2001) philosophical insight: “A scholars’ rock … is a little piece of a wrinkle from which you can image the whole wrinkle; it’s a little piece of a rock from which you can imagine the whole rock; it’s a little piece of mountain from which you can imagine the whole mountain—and so on” (p. 39). Based on Ying Bao’s (瑛寶, late 18th–early 19th century) inscription on his, Painting of a Rock from Mt Pan, Rosenblum (2001) clarifies that the literal meaning of lou is “to leak” and the desired attributes of lou is “a pitted surface with depressions and hollows of various sizes is preferred” (p. 143). Taking this notion of hollowness a stage further is the principle of tou, described by Rosenblum (2001) as “holes that reach all the way through, admitting the light and air” (ibid.). The interest behind both of these desirable attributes is the idea that the non-visible inner world of a stone can be tapped into through natural tunnels and hollows so that a viewer may see inside, or, as Rosenblum (2001) proposes, “for a paradise inside” (p. 103).

… the Chinese look at the world as having five directions—north, south, east, west, and ‘in.’ And ‘in’ is more important to them than north, south, east and west, because the center—the ‘in-space’—is where all the other directions emanate from. (p. 99)

Fascination with capturing the

sense of ugly beauty when looking into stone is not, of course, restricted to

the Orient. In Part 2 of this discussion I will address how Occidental artists

have also engaged with the idea of beauty inside stone.

_________________________

1 Some writers prefer the term

“scholars’ rock.” William Benz (1996), in The

Art of Suiseki: Classic Japanese Stone Gardening, advises that there is a difference between stones and rocks:

In ordinary

language, we use the word ‘stone’ as a general term for all of the solid parts

of the earth’s crust. … In the science of geology, however, we speak of

minerals and rocks rather than of stones. A rock is an aggregate of several

minerals created through a natural process. It is not a homogeneous piece of

the earth’s crust. (p. 83)

While not disputing such an

important technicality, I choose to use the term “scholars’ stone” for the

beauty of the alliteration of the “s” sounds and my belief that few readers are

likely to quibble about the difference between a stone and a rock.

2 Rosenblum, Richard 2001, Art of the Natural World: Resonances of Wild

Nature in Chinese Sculptural Art. MFA Publications, Boston

3 Hu, Kemin 2002, The Suyhuan Stone Catalogue: Scholars’ Rocks

in Ancient China

4 Covellow, Vincent T & Yuji

Yoshimura 2009, The Japanese Art of Stone

Appreciation: Suiseki and its Use with Bonsai. Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo