Martin Rota (aka Martino Rota; Martin Rota Kolunić; Martinus

Rota Sebenicensis) (c.1520–83)

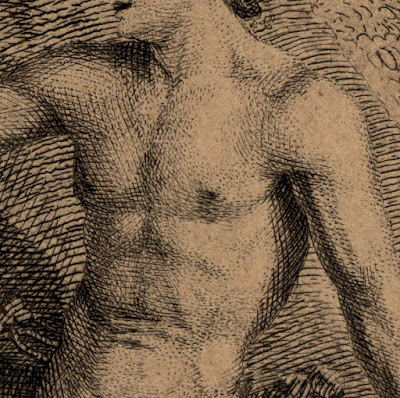

“Christ as the

Man of Sorrows", 1568,

published by Nicola Nelli (c.1530–post 1576)

Engraving on

fine laid paper, trimmed at the platemark, marked with the monogram of the

publisher “NN” (Nicola Nelli), dated on the plate at centre of lower edge, “1568”,

and lettered on the side of the sarcophagus cover (partly decipherable) with the acronym: “M · R · S · F” (Martin Rota Sebenicensis

Fecit)

Size: (sheet)

17.1 x 13.4 cm

Condition: this

is a print of the utmost rarity (it may even be a unique copy) with a few very

small abrasions otherwise in excellent condition. The sheet is trimmed to the

platemark and there is a pint hole towards the lower right corner. There are

ink and pencil inscriptions (verso) along with a collector’s stamp “FA.”

I am selling

this small masterpiece for a total cost of AU$460 (currently US$347/EUR324.81/GBP276.78

at the time of this listing) including postage and handling to anywhere in the

world.

If you are

interested in purchasing very rare, museum quality print, please contact me

(oz_jim@printsandprinciples.com) and I will send you a PayPal invoice to make

the payment easy.

This print has been sold

This simple but

very beautiful engraving has almost been the death of me over the last three

days. As an act of sharing my woes and unburdening my angst onto others, I’ve

decided to give an account of my adventures.

My journey of

discovery began when I decided to separate the sheet from the backing board

onto which it was glued. I needed to do this operation as I could see glimpses

of inscriptions on the back of the sheet that looked interesting and, more

important, the glue used for attaching the sheet to the backing board had

stained its way through to the front of the sheet marring the image. For this

operation, I simply laid the print and its backing board in a bath of water

(with no chemical additives) for an evening dip. In the morning I was relieved

to find that the print was floating above the backing board and the glue (whatever

it was) had dissolved away completely and even the stain on the front of the

image had miraculously disappeared. Marvellous.

After drying

the print, I examined its back. At the very top of the sheet (verso) I saw

pencils numbers that I assumed were a collector’s catalogue references and

below them, an ink inscription written in an old but dreadful hand that I assumed

to be a previous collector’s name: “Grauwels Bruse”. Further down, I saw an

ink-stamped monogram of entwined initials, “FA”, no doubt another past

collector, but my interest didn’t lead me to try to identify who this might be.

Instead my eyes were fixated on the pencil inscription: “Martin Rota

Sibenicensis fecit.” This name seemed to verify that the print was by Rota as I

had purchased it from a dealer as a genuine Rota. Alas, this is the beginning

of my woes.

I consulted the

Bartsch catalogue raisonné for Rota (1979, Vol. 33) never expecting even for a

moment that I would have difficulty in finding the print with its title and Bartsch

number. I was in shock, however, as it wasn’t there. I then checked on the

British Museum’s holdings of Rota prints and they didn’t have it either. I then

checked everywhere and no museum had this print. I was VERY uneasy!

Next, came the

painful process of verifying that this print was a genuine Rota despite the

fact that it wasn’t listed ANYWHERE. And so began the painstaking process of

comparison of small details in this print with verified—Bartsch approved—prints

by Rota. At this point, I can say with deep satisfaction that I now know more

than I did before about the way that Rota renders woodgrain on crosses. Moreover,

from endless comparisons with other artists’ versions of “Christ as the Man of

Sorrows” executed in much the same time period, I now know that very few

artists portray Christ with a well-toned six-pack as depicted by Rota in his

prints. For example, Israhel van Meckenem (c.1445–1503) in his “Gregorian Man

of Sorrows” (Bartsch 9[6].135[251]) shows Christ with a stretched and sunken

abdomen appropriate for a man who has just been crucified.

The final stage

in my research should really have been the first stage: to study the

inscriptions on the print itself. Up to this stage I had ignored the lettered “NN

exc” inscribed on the side of the tomb as I had assumed that it simply signified

the publisher name, Nicola Nelli, and had little bearing on the name of the

engraver. Of course I was wrong. After consulting the list of 16th

century publishers in “Prints after Giulio Clovio” (1998, see p. 133) I

discovered that Nelli SPECIALISED in publishing Rota’s prints (among other

artists). What also surprised me is that Nelli executed prints in the style of

Rota but “the drawing is inferior to Rota’s” (ibid).

When I read

this remark, depression hit me in the sense that I then assumed that Nelli not

only published the print but also engraved it. The other featured letters shown

on side of the tomb’s cover, “M · R · S · F”, I had no idea what they could

mean. That is, until the thought occurred to me that that they were the first

letters of Rota’s name, an acronym for “Martin Rota Sebenicensis” and the final “F” signifying the all-important

piece of information: Fecit” (i.e. the print was executed by Rota).