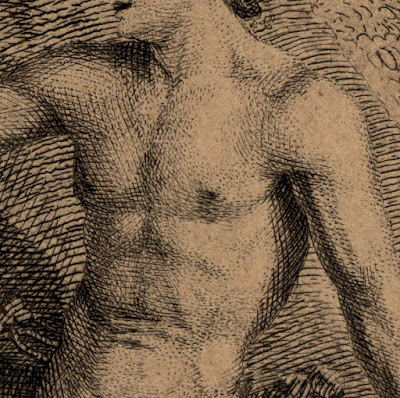

Johann Elias Ridinger (aka Johann Elias Riedinger)

(1698–1767)

“Adam names the

Animals” (Genesis 2. 19. 20: “The man gave names to all livestock, and to the

birds of the sky, and to every animal of the field; but for man there was not

found a helper suitable for him.” [Word English Bible]), 1745, published in Augsburg

1767, from the series, “Das Paradies oder die Schöpfung und der Sündenfall des

ersten Menschenpaares (Paradise: the Creation, the fall of man and the expulsion

of the first couple of man“)

The British

Museum offers the following description of this series and its publication:

“A bound

portfolio containing twelve prints illustrating Adam and Eve in Paradise; the creation

and fall of man. c.1730–60 Etching with some engraving; in the original blue

wrapper”

Etching and

engraving on heavy brown paper.

Size: (sheet) 43.5

x 63.5 cm; (plate) 39 x 53.5 cm; (image borderline) 35 x 52 cm

Each sheet in

the Paradise series is lettered with bible quote inscribed in German, French

and Latin and lettered with production and publication detail: “Ioh. Elias Ridinger

invenit fec et excud. A V.

Thienemann 1856

807-181 (Georg Thienemann 1856, “Johann Elias Ridinger, Maler und Kupferstecher,

nach Seinem Leben un Wirken”, Leipzig, Rudolph Weigel); Nagler 6

Condition: exceptionally

rare and near faultless impression printed on brown paper with margins as

published. There are remnants of mounting tape (verso)

This print has

been sold along with the other plates from the Paradise series

(which I will be

posting soon)

This print shows

the very first sunrise as described in the Old Testament with Adam broadly

gesturing to the rich diversity of animals filling the Garden of Eden.

Ridinger

clearly wanted this and the other plates from his “Paradise” series to be an

ultimate statement about God’s handiwork; after all the conspicuous consumption of time committed to the plate is plain to see. Ridinger certainly ensured that every square inch of this particular plate

is “filled to the brim” or, to borrow another phrase, “packed to the rafters”

with every critter imaginable. Not only do they seem to struggle to be in our

view but many of them interact with each other with a slight hint of territory

marking.

Leaving aside

the shameful idea proposed to me that these animals are slightly eroticised and

question Adam’s interest in them—mindful that Eve has not set foot in the

garden at this point in the story—my interest centres on the birds in the sky.

My interest in these birds is that at the time when this print was being

executed the world was beginning to hear about the Birds of Paradise in New

Guinea. More exciting than this, a marvellous folklore had arisen that such

birds never landed but spent their lives perpetually flying in a sky paradise

with their eggs and young ones tucked safely in their feathers.

Regarding the

significance of this print and the others of the series, an interesting website

that discusses Ridinger’s plates is “Niemeyer’s AHA! Events” (December

2013) which offers the following insight into Ridinger’s aim:

“‘… to show the

manifold zoological manifestations, the presentation of carefully painted

native and exotic animals’, the latter he had become acquainted with as court

painter of emperor Rudolph II, at once setting himself apart from the majority

of the Dutch colleagues who had to confine themselves to domestic animals.”

(http://aha.luederhniemeyer.com/aha1312e.php;

the in text quote may be from Kurt J. Müllenmeister’s “Roelant Savery” / Die

Gemälde. 1988)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please let me know your thoughts, advice about inaccuracies (including typos) and additional information that you would like to add to any post.